- Home

- Cyrus Mistry

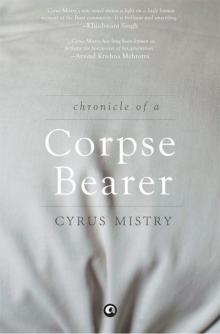

Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer

Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer Read online

‘Cyrus Mistry’s new novel shines a light on a little-known segment of the Parsi community. It is brilliant and unsettling.’

—Khushwant Singh

‘Cyrus Mistry’s narration blends measured doses of black humour, irony and tragedy. His characters are real people, and stay with the reader way after the last page has been turned.’

—Robin Shukla, Afternoon Despatch & Courier

‘[Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer] is an unflinching look at the lives of the nussesalars—the dirty little secret of the otherwise admirable Parsi community—which is presented through a combination of heartbreaking candour and occasional ribald Parsi humour.’

—Anvar Alikhan, India Today

‘Mistry weaves together the all-important topics of love and death in a chimerical, magical world which the reader will remember long after he puts down this book.’

—Ira Trivedi, The Asian Age

‘Mistry’s pellucid prose, with many a memorable metaphor, makes for delightful reading. What lifts this narrative to greater heights is Mistry’s insight into Elchi’s milieu and mind. Peppered with grey humour, irony and tragedy, this well-crafted book is a winner.’

—Bakhthiar K. Dadbhoy, Outlook

About the book

At the very edge of its many interlocking worlds, the city of Bombay conceals a near invisible community of Parsi corpse bearers, whose job it is to carry bodies of the deceased to the Towers of Silence. Segregated and shunned from society, often wretchedly poor, theirs is a lot that nobody would willingly espouse. Yet thats exactly what Phiroze Elchidana, son of a revered Parsi priest, does when he falls in love with Sepideh, the daughter of an aging corpse bearer...

Derived from a true story, Cyrus Mistry’s extraordinary new novel is a moving account of tragic love that, at the same time, brings to vivid and unforgettable life the degradation experienced by those who inhabit the unforgiving margins of history.

About the author

Cyrus Mistry began his writing career as a playwright, freelance journalist, and short story writer. His play Doongaji House, written in 1977 when he was twenty-one, has acquired classic status in contemporary Indian theatre in English. One of his short stories was made into a Gujarati feature film. His plays and screenplays have won several awards. His first novel, The Radiance of Ashes, was published in 2005.

By the same author:

FICTION

The Radiance of Ashes

PLAYS

Doongaji House

The Legacy of Rage

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

This digital edition published in 2013

First published in India in 2012 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright © Cyrus Mistry 2012

All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to any actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, print reproduction, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Aleph Book Company. Any unauthorized distribution of this e-book may be considered a direct infringement of copyright and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

e-ISBN: 978-93-82277-85-9

All rights reserved.

This e-book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form or cover other than that in which it is published.

For Jill and Rushad

GAP PAA.ORG

One

‘Oi, Elchi, you bloody drunkard! Still lolling in bed?!’

There was no sound more revolting or hateful to the ears than that voice which plucked me rudely from my garden of dreams.

I was under the bower of the giant banyan with Seppy. Of all our numerous hideouts in the forest, this was her favourite. But in that instant, when Buchia’s hideous falsetto impinged on my consciousness, she was gone.

A wretched fatigue hugged every inch of my body like a lover. On my threadbare mattress, I clung to traces of remembered sweetness, longing for more sleep, but knew it would be denied me. . . The flimsy front door of my tenement was being slammed and rattled with an ugly insistence. Presently, the odious shrieking came again:

‘Two minutes is all I’m giving you! Not out by then, straightaway I’m dialling Coyaji’s number. And so much the better if he’s mad for being woken at this hour. . .I’ll tell him everything: fucking corpses have begun to stink, mourners are congregating, but your chief khandhia’s still in bed, pissed out of his skull.’

Abusive harangue, the crunch of footsteps on gravel. . .both receded.

Oh fuck you Buchia, you aren’t paying for our drinks, are you? No time for a sip of water, let alone a tumbler of booze.

Rustom and Bomi would have given anything for a quick stopover last night—all of us deadbeat after walking those six miles to Laal Baag and back with a stiff more corpulent than most—but even simple-minded louts like us know better than to leave a corpse unattended on the pavement while guzzling at an illicit den. So, we hit upon a compromise: resting one end of the bier against a compound wall, Fali’s brainwave this, Bomi ran in and purchased a bottle. Snugly secured between the corpse’s stout legs for the remainder of our jaunt, it had to be pried out with some force once we deposited the body in the washroom of the allotted funeral cottage.

Now how is that any of your business, bloody Buchia? Those damn biers we lug around—solid iron—each weighs nearly eighty pounds! And all corpses aren’t emaciated by death, let me tell you. Some positively swell, growing more flaccid by the minute. Besides, how else, I ask you this, how else are the best of us to keep up this carrion work, this constant consanguinity with corpses, without taking a drop or two? The smell of sickness and pus endures; the reek of extinction never leaves the nostril.

Good sport that he is, Fardoon waited until I had knocked back my share of the booze before joining me for the arduous job of washing the man mountain. Fardoon doesn’t drink.

It’s a job that takes courage and strength, believe you me— rubbing the dead man’s forehead, his chest, palms and the soles of his feet with strong-smelling bull’s urine, anointing every orifice of the body with it before dressing him up again in fresh muslins and knotting the sacred thread around his waist. All the while making sure the pile of faggots on the censer breathes easy and the oil lamp stays alive through the night; all this, before we retire ourselves well past midnight. So what’s your fuckin’ fuss about, you bastard of a Buchia?

One side of my head was throbbing, raw; felt a bit of a corpse myself. Then my eyes lit on the wall clock: twenty past six already!

Early morning silence punctuated by a tittering of birds soothed my nerves, but the muscles still ached. . . Outside the wire-meshed window, a sprig of pale orange bougainvillea swayed slightly. As I climbed out of bed, the rays of a fledgling sun touched the treetops lightly with a golden brush. The sky was deep blue and softly luminous, without a speck of cloud. Had I really woken up from dreaming? Or was this a dream I was waking to?

How beautiful and peaceful is this place—much of the time, at least—where the faithful consign their dead to the vultures in a final act of charity, their bones pulverized by the sun, then washed away. . .subsumed in the el

ements.

I grew up not far from here. When I was still a child, I may have been brought along by my parents to attend a funeral or two; but it was only much later I began to see this as my garden, my own private forest: an enchanted place in which I was free to roam, marvelling at leisure at the shapes, smells and colours of nature, the magnificent trees, birds, bushes and all that rocky wilderness.

Near the hill’s summit brood the squat towers—three in number—their jaws open to the sky, allowing birds of prey to descend and eat their fill, then fly up once more, unhindered. Surrounded on every side by a town that grows more noisy and populated by the day, this estate is so vast and secluded that no syllable of human voice or activity grates upon its timbre of peace. Though death is its precise reason for existence, in this garden, life—overwhelmingly—is the victor.

I first set eyes on my Sepideh in the forest on the hill. Even the most fleeting remembrance of Seppy can bring tears to my eyes—so evanescent her presence, so brief our togetherness.

This was her home, in a more literal sense than I realized when I first saw her. I had caught glimpses of her before—wandering through overgrown banyan vines, running, once, at breathtaking speed after a peacock through tall grass. I didn’t know then she considered animals her dearest friends. She fed as many as she could every day, often by her own hand: wild squirrels, pheasants, pye-dogs, stray cats, as though they were her personal pets.

The first time I approached her she was stooped to the ground placing a small bowl of milk in a clearing.

‘Who’s that for?’ I asked, as she straightened herself.

She was shy and only smiled without meeting my eyes; but after a moment answered:

‘A snake. A big grass snake who comes and drinks it all up, whenever I have any to spare.’

Lovely as the breeze wafting through the trees, just as light and feathery, she seemed to me a gawky, yet beautiful child of nature, completely at home in these woods in which I befriended her, and later, became her lover. Seven years have passed since then. . .

Already I feel like a pack animal. I am twenty-six years old and strong as an ox, but the work’s definitely telling on me, on each of us. . . No, I don’t mean the physical strain—that can be rough, no doubt—so much as the contempt and abuse we receive for doing a job no one else will touch.

Can’t deny I always knew it would be rough. It’s more than most people can stomach, many had warned me: let alone you, the coddled son of a priest. But in those first years, Seppy was at my side. Nothing, not the direst predictions of ruin and misery could have kept us apart. People said it was disastrous for first cousins to wed, that our children would be cretins! But we never felt we had a choice, you see. And never once in those seven years did I ever feel let down, or regret my decision. Nor did she, for that matter. Every evening, returning home from work, the happiness that gleamed in her eyes salved my every ache and bruise, healed the smarting of swallowed insults. In our mealy, narrow cot at night, her love refreshed and rejuvenated my body. And all that alarmist talk came to nought; our child was born perfectly normal.

But now, Seppy’s no longer with me. . . And even in dreams I don’t see her so often. Dull nausea swelled and passed as it did every morning when I woke to the certain knowledge of being alone. My heart ached with longing for the woman who had taught me how to love; but I was running late. . . I threw a crumpled muslin gown over my night clothes, slipped into my white cloth bootees and cloth cap, both essential accessories of my uniform, and knotted the strings on my face mask. I paused for only an instant to gaze at my three-year-old curled up in a corner of her mattress. Unmoved by Buchia’s ruckus, she was still engrossed in a deep sleep. A fierce surge of tenderness shuddered through my body, and I swore on Seppy’s sweet forehead to protect her, always.

‘Come son, your tea’s getting cold. . .’

Temoorus’s living quarters abutted my own, separated by no more than half a wall of exposed brick and flaking plaster, and a thatched veranda. He would have heard Buchia’s screaming, and got a cup of tea ready for me. Not so much from the kindness of his heart, I should say, as to hasten me off to work so he can have my little one all to himself when she wakes. It annoys me how possessive he grows, day by day.

Crossing the threshold that divides our homes, I came face to face with Temoo: seated, as always, in his square, rattan chair, in the same pair of striped pajamas I’d seen him wearing for weeks now; the same translucent vest with the ripped sleeve that revealed his dark, hairy body: a thin, vulpine man of scruffy habits, made ridiculous by age, and an incongruous tumescence at his abdomen. Since Seppy’s death, we’ve been thrown together a lot—I depend on him much more now, I do—but try never to forget I shouldn’t trust him an inch. Yet nearly every day of the week, for several long hours, I am compelled to leave in his custody the most precious portion of my being: my baby, Farida. Simply, I have no option.

A large mug of tea stood on the small teapoy beside him, covered with an upturned saucer.

‘Behnchoad Buchia woke me from such a deep sleep,’ said Temoorus. ‘Bullying and yelling his head off first thing in the morning! What that bastard needs. . .no, I won’t say it. . .’

‘What. . .?’

‘Don’t like to start my morning with swear words, but really, a bamboo up his arse. All the bloody way. . .’

‘I’ll drink to that,’ I said, swallowing a generous swig of lukewarm tea. ‘Six corpses, yesterday! No joke, Temoo, lugging them in from all over town. And on top of it, the joker claims we came back sozzled.’

‘Fucking slob doesn’t know his arsehole from his gob. Stinks up the place with his farts and his taunts. What that man needs is a good hiding, but who’ll give it to him, I ask you? He’s our warden. . .our boss. Who’s going to question the boss?’

‘Not to fret, my boys!’ said a voice over our heads. ‘Just leave it to the One-Above. . .’

We looked up and saw Burjor, leaning over his balcony. But he wasn’t speaking of himself.

‘Time will come for that man, too, when he will choke on his wickedness—mark my word, boys—bleed remorse.’

Once a bodybuilder, this fair-skinned and still handsome corpse bearer had suddenly lost an alarming amount of weight in recent months, and much of his proud swagger. Though he grew feebler by the day, and his clothes had started to hang loosely on him, he remained rather self-conscious of his looks—the prominent, clean-shaven rock jaw, the thickset, well-trimmed moustache, green eyes—what’s more, Burjor never once complained about life’s unfairness. He remained confident of the infallible perfection of the divine master plan. He now declared, in the dramatic and slightly pompous fashion he’s given to:

‘One-Above watches everything, mind you. That maaderchoad’s days are numbered.’

Was I imagining it, I wondered, or had a furtive edge of bitterness crept into Bujji’s voice of late?

‘Oi, Bujji!’ yelled Temoo hoarsely, ‘don’t wreck your morning bad-mouthing excrement.’

‘Well, someone has to flush a turd into its pit and bury it. Too much stink. . .too many flies. . . Am I right or am I wrong? Tell me?’ chuckled Bujji. ‘If I had any strength left in my body, I’d do it myself.’

Like Bujji, everyone at the Towers had some reason to hate the man we were talking about. His real name was Nusli Kavarana, but his treatment of us menials was so sadistic that he was universally known as Buchia, or the ‘Corker’. He was some sort of labour contractor, directly in charge of hiring and firing us corpse carriers as well as all the maintenance staff on the estate; but very thick with Coyaji, the Punchayet’s secretary for gardens. God knows what sort of deal those two had struck up, but somehow, Buchia had become an inviolable fixture in the Towers’ establishment.

‘Now today, God knows what sort of day it’ll be,’ I said, resuming my conversation with Temoo. ‘Do you? I mean, have you heard anything at all? Bloody hell, so many Parsi corpses in one day is just not natural.’

‘Paper

s say certain districts have seen an outbreak of gastro: Parel, Dockyard, Khetwadi. . .but these things have happened before. Shouldn’t last more than a few days.’

‘Gastro?’

‘That’s only the official euphemism, boys: more likely cholera,’ interjected Burjor from above; then, with apocalyptic finality, he turned to go in, saying, ‘But no one, mind you, knows just how bad. . .and it could last longer than just a few days. . .mind you.’

‘So much fanfare about that bloody hearse they bought— insertion in Jam-e-Jamshed and all—gone phut already?’ I asked Temoo.

‘At the garage being repaired, son,’ he replied. ‘Engine trouble, claims Buchia, but my point is, whether it’s cholera, or gastro, or whatever, they’d better hire more khandhias. You guys should refuse to work like this. Sixteen hours, eighteen hours. . .! And especially, you, a nussesalar! In my time, no hearse, no nothing. But we never saw more than two, at most three corpses in a day. Oh yes, there was another time, much worse than this, even earlier. . .in my father’s day. . .’

It had always been a hereditary profession. Generations of inbreeding within families belonging to the small sub-caste of corpse bearers—together with a self-imposed and socially enforced isolation—had rendered them freakish, awkward and genetically unsound. How completely sad and despairing then, that corpse bearers continue to squirm and thrash about while trying to find ways to escape its inherited tyranny. My own case was completely unusual, of course: people were usually shocked and disbelieving when they learned that I voluntarily chose to marry a khandhia’s daughter, opting for a life at the Towers of Silence.

Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer

Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer